from E. M. Forster’s Aspects of the Novel:

Chapter 2: THE STORY

WE shall all agree that the fundamental aspect of the novel is its story-telling aspect, but we shall voice our assent in different tones, and it is on the precise tone of voice we employ now that our subsequent conclusions will depend.

Let us listen to three voices. If you ask one type of man, “What does a novel do?” he will reply placidly: “Well—I don’t know—it seems a funny sort of question to ask—a novel’s a novel—well, I don’t know—I suppose it kind of tells a story, so to speak.” He is quite good-tempered and vague, and probably driving a motor-but at the same time and paying no more attention to literature than it merits. Another man, whom I visualize as on a golf-course, will be aggressive and brisk. He will reply: “What does a novel do? Why, tell a story of course, and I’ve no use for it if it didn’t. I like a story. Very bad taste on my part, no doubt, but I like a story. You can take your art, you can take your literature, you can take your music, but give me a good story. And I like a story to be a story, mind, and my wife’s the same.” And a third man he says in a sort of drooping regretful voice, “Yes—oh, dear, yes—the novel tells a story.” I respect and admire the first speaker. I detest and fear the second. And the third is myself. Yes—oh, dear, yes—the novel tells a story. That is the fundamental aspect without which it could not exist. That is the highest factor common to all novels, and I wish that it was not so, that it could be something different—melody, or perception of the truth, not this low atavistic form.

For the more we look at the story (the story that is a story, mind), the more we disentangle it from the finer growths that it supports, the less shall we find to admire. It runs like a backbone—or may I say a tape-worm, for its beginning and end are arbitrary. It is immensely old—goes back to neolithic times, perhaps to palaeolithic. Neanderthal man listened to stories, if one may judge by the shape of his skull. The primitive audience was an audience of shock-heads, gaping round the camp-fire, fatigued with contending against the mammoth or the woolly rhinoceros, and only kept awake by suspense. What would happen next? The novelist droned on, and as soon as the audience guessed what happened next, they either fell asleep or killed him. We can estimate the dangers incurred when we think of the career of Scheherazade in somewhat later times. Scheherazade avoided her fate because she knew how to wield the weapon of suspense—the only literary tool that has any effect upon tyrants and savages. Great novelist though she was,—exquisite in her descriptions, tolerant in her judgments, ingenious in her incidents, advanced in her morality, vivid in her delineations of character, expert in her knowledge of three Oriental capitals—it was yet on none of these gifts that she relied when trying to save her life from her intolerable husband. They were but incidental. She only survived because she managed to keep the king wondering what would happen next. Each time she saw the sun rising she stopped in the middle of a sentence, and left him gaping. “At this moment Scheherazade saw the morning appearing and, discreet, was silent.” This uninteresting little phrase is the backbone of the One Thousand and One Nights, the tape-worm by which they are tied together and the life of a most accomplished princess was preserved.

We are all like Scheherazade’s husband, in that we want to know what happens next. That is universal and that is why the backbone of a novel has to be a story. Some of us want to know nothing else—there is nothing in us but primeval curiosity, and consequently our other literary judgments are ludicrous. And now the story can be defined. It is a narrative of events arranged in their time sequence—dinner coming after breakfast, Tuesday after Monday, decay after death, and so on. Qua story, it can only have one merit: that of making the audience want to know what happens next. And conversely it can only have one fault: that of making the audience not want to know what happens next. These are the only two criticisms that can be made on the story that is a story. It is the lowest and simplest of literary organisms. Yet it is the highest factor common to all the very complicated organisms known as novels.

Chapter 5: THE PLOT

Let us define a plot. We have defined a story as a narrative of events arranged in their time-sequence. A plot is also a narrative of events, the emphasis falling on causality. “The king died and then the queen died,” is a story. “The king died, and then the queen died of grief” is a plot. The time-sequence is preserved, but the sense of causality overshadows it. Or again: “The queen died, no one knew why, until it was discovered that it was through grief at the death of the king.” This is a plot with a mystery in it, a form capable of high development. It suspends the time-sequence, it moves as far away from the story as its limitations will allow. Consider the death of the queen. If it is in a story we say “and then?” If it is in a plot we ask “why?” That is the fundamental difference between these two aspects of the novel. A plot cannot be told to a gaping audience of cave men or to a tyrannical sultan or to their modern descendant the movie-public. They can only be kept awake by “and then—and then—” They can only supply curiosity. But a plot demands intelligence and memory also.”

From E.M. Forster’s Clark Lectures “Aspects of the Novel,” Trinity College,

Cambridge University, 1927

Journal Entry vs. Story (or, What I Did This Weekend vs. Conflict-Crisis-Resolution):

Young writers often ask about the difference between writing a journal and writing a story, a question that highlights what I consider to be one of the fundamental elements of good writing, and something that I return to time and again in writing workshops. Beginning writers are prone to write what I refer to as “what I did this weekend” stories. Nothing wrong with that, it’s part of the learning curve when learning the craft of writing. And what all of these “what I did this weekend” stories have in common is that they are of no interest to anyone but the writer. There is a reason for this: it is because these stories do not give the reader anything back in return for their reading.

When a reader picks up a story, there is an implied contract between reader and writer. The contract states that the reader will devote her time to a close and careful reading of this narrative, and the writer will not waste that time, but will instead provide a worthwhile reading experience. This is, of course, a one-way contract, since by the time the reader picks up the text, the writer is no longer involved. But if the reader reads two pages and finds that the writer has broken the contract, the reader will break it, too, by putting it down.

There are many ways for a writer to break the contract. For example, if you are telling a story from the 1st Person Point-of-View (POV) of a four year old, then you must use the language of a four year old. Once that four year old says “Daddy came into the kitchen and took the blender from Mommy, exerting his habitual plenipotentiary control over our family,” you have broken the contract, because four-year olds do not think or speak like this–the “spell” is broken.

Another way to break the contract is to do as I have described, to present the reader with a “what I did this weekend” narrative. What I did this weekend is nice, weekends are good, but why should a reader care what I did this weekend? Well, they might, if what I did is presented as a plot, with a beginning, middle, and end, and with a character the reader can identify with and care about, who makes a choice at the crisis moment that will change him forever. For most of us, our lives do not really fulfill this narrative arc, and we do not want them to. We don’t want to live every weekend having conflict and crisis and resolution of the kind that good stories are made of. Why not? Because that’s a lot of tension and anxiety, and our lives are way more comfortable without all the trouble.

But, in fiction (in nonfiction too), only trouble is interesting. Unless there is a character who has some desire, and a conflict preventing her from attaining that desire, and a crisis, choice, and resolution, the story is not going to provide the dramatic arc that readers expect when they pick up a story. We don’t want this kind of trouble in our lives; but we demand it in our stories.

Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, widely considered one of the best novels of the 20th C., is also what is known as a Roman á Clef, a French phrase that means a ‘book with a key.’ This is a book whose fictional characters are all based on real people, and if you know which real person each character is based on, then you’ve got the ‘key.’

Hemingway went around Europe with his ‘lost generation’ expatriate friends after WWI, and he wrote his novel based on their exploits. However, the exploits of a handful of expats in Europe would not make for a story with the narrative arc that a novel requires. So, Hemingway did as all writers have been doing for centuries, he changed the real events so that they would provide the reader with a satisfying narrative arc.

It is early in the process to worry too much about these things, but it cannot hurt to have them in the back of your mind as you wrestle with the difference between writing a journal and writing a story, and other matters concerning the craft of writing.

So, what is this ‘Conflict-Crisis-Resolution’ that I’ve been writing about? Here it is in a nutshell:

ANALYZING PLOT: CONFLICT-CRISIS-RESOLUTION (FREYTAG’S PYRAMID):

Two stories that illustrate the ways that conflict-crisis-resolution can work in the best fiction are Ambrose Bierce’s “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge” and James Joyce’s “Araby.” Each appears at the end of this chapter, and each contains the essential elements of the short story. What are these elements?

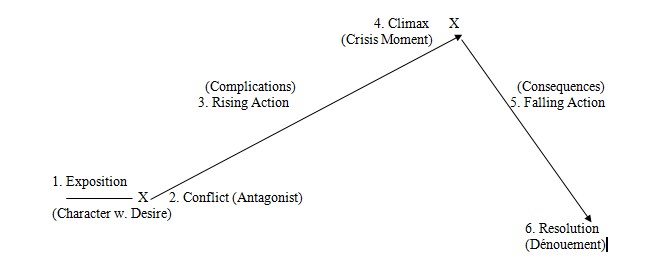

At the beginning, we want to be introduced to a Protagonist with a Desire (this necessary introductory information is called Exposition). We want a Conflict that impedes the attaining of that goal or desire (Antagonist); this conflict gets worse through what we term a Rising Action, which essentially contains Complications that further obstruct the goal or desire, and then we have a Crisis Moment, when something has to ‘give.’ Usually, at this moment, the protagonist must make a Choice, and that choice changes everything, and brings about a Falling Action, which essentially contains the Consequences that flow from that choice, resulting in a Resolution.

1. Protagonist with Desire (Exposition)

2. Conflict Obstructing that Desire (Antagonist)

3. Rising Action (Complications)

4. Crisis Moment (Choice)

5. Falling Action (Consequences)

6. Resolution (Dénouement, or Ending)

If you examine any short story that you admire you will find it contains these elements in one form or another. It has been diagrammed in various ways, including the one below:

It is important to have a handle on this when putting together your story, and it can be as simple as a character who wants to be accepted by the ‘in’ crowd, who is conflicted because it means doing things that go against her beliefs and upbringing (smoking, drinking, etc.). There are complications when she falls in love with one of the guys in the ‘in’ crowd, and he further prods her to do these things, until finally she has to make a choice. Whatever she decides, she will be changed, and a reader wants to see a change in their heroes, whether for better or worse, because the character becomes human through this process, and we can relate to her.

Let’s have a closer look at each of these:

1. Exposition (Character w. Desire):

We want a character with a desire. There are broad desires and big desires and little desires, and in a short story we want the little one. Why? Let’s take an example: Morgan wants to build a hospital in her impoverished homeland; that’s a big desire. In a short story, the chances are that she’s not going to get that hospital built by the end of the story. That’s the Express Train desire, going all the way. Too big.

On the other hand, in order to begin the process, she needs a bank loan. That’s a much littler desire, and one that can certainly be resolved one way or the other by the end of the story. That’s the Local Train, making all the stops; first stop: loan approval.

It doesn’t matter how small the desire is, it only matters that your character wants it badly. You can have two characters in the middle of the Sahara Desert with only one canteen of water, and they both want it. They must want it equally, too; the more one wants it, the more he will do to attain it. It only works if the other character wants it equally as much, and is willing to do equally as much, or more, to attain it. That raises the cost, raises the stakes, raises the suspense, raises the tension. In a story, in any story, from the moment the character with desire is introduced until the moment of decision (the climax – the point of no return), you want to keep the stakes as high as you can (more on that with Rising Action, below).

Oh yes, what about that broad desire I mentioned above? That is a different way of looking at desire: not what the character wants, but why? Why does Morgan want to build a hospital in her homeland? Did her sister die there when they were children from lack of proper health care facilities? Does she have something to prove to the people back home? So there is always a what and a why. The what is tangible, physical, attainable; the why is internal, psychological, emotional.

2. Conflict (Antagonist):

It’s no good if your hero’s Mom is the bank president and the loan approval is quickly procured by a phone call from the loan officer. Nothing is risked, nothing can be lost, it’s too easy. Moreover, it doesn’t involve trouble, or suspense. Print and hang this somewhere near your writing desk: good writing always requires trouble and suspense. Janet Burroway, in Writing Fiction: A Guide to Narrative Craft, wrote: “Only trouble is interesting.”

So, your desire is the loan approval and your conflict is….what, exactly? Well, bank loans are not easy to get, ever, and especially in today’s economic climate (if your story is set in the present, but more on Setting later). So, the conflict is pretty much built into the desire in this case. And you must increase the conflict, raise the stakes, make it more suspenseful. How can you do that? Supposing that your protagonist wants to build her hospital on a plot of land that the government has set aside for just such a project, but the public land reform act expires at the end of the year, and the story begins on December 12th. If she doesn’t post a bond and break ground by December 31st, the land reform act expires and the land reverts to the adjoining wildlife preserve. She hasn’t even done anything and already the conflict is greater than when we began: time is running out. You will find that time and space are your allies in creating tension and suspense in a narrative. For example, if you have two siblings who ‘hate’ each other, but they are on a cross-country drive to see their dying father, you have built-in tension: there is no getting out of that car!

3. Rising Action:

A ‘Rising Action’ is just what it sounds like, something is being raised. What? We mentioned these before: stakes, tension, suspense. We need to keep raising these until the moment of truth, the point of no return, when something has to give (more on this in the Climax section below).

So, we’ve got a protagonist (let’s call her Morgan) with a Desire (loan approval) and a Conflict (loans are hard to get, plus time is running out). How can we raise the stakes? Simple: we make it increasingly difficult for Morgan to achieve her desire by placing obstacles in her way. There is a “C” word for these obstacles that comprise the Rising Action: Complications.

Suppose you open your story at the bank, with Morgan sitting across the desk from the loan officer, let’s call her Ms. Stanley. And she’s flipping through Morgan’s file, looking at the application papers and so forth, and she stops and looks up.

“Miss Morgan,” she said. (I guess our protagonist’s name is Morgan Morgan. Oh well.)

“Yes?”

“I see here that your credit rating is very low. We would never grant a loan based on this rating.”

There, that’s a rising action, a complication, her credit rating is too low. But wait, for every complication there is a solution:

“Wait,” Morgan said, and pulled a brown leather wallet from her bag. “That’s probably Morgan J.P. Morgan. His credit rating fell off a cliff. But I’m Morgan M. Morgan. Can you check again?”

“Oh, Morgan M. Morgan,” Ms. Stanley said. “All right, give me a sec.”

So there you have a reversal of fortune. If you have studied Greek tragedy (which you should, if you want to learn about the craft of writing) then you have heard this term, and the Greek word that describes it: peripeteia, a sudden reversal of fortune or change in circumstances.

Close call, but our hero is off the hook, a narrow escape. But wait, there’s more, because that’s not enough, it’s too easy. Let’s return to the scene (yes, this is what we call a ‘scene,’ it has characters and dialog; more on scenes later).

Ms. Stanley flipped more pages and stopped once more.

“Morgan M. Morgan?” she asked.

“Yes,” Morgan said. “That’s me.”

“But I see here that you were arrested for assault, and it does say ‘Morgan M. Morgan.”

Uh-oh, another complication.

“Yes, that is me,” Morgan said. “But I can explain.”

“I’m sure that you can, Miss Morgan, but our bank has a strict policy. This says you assaulted a man and caused serious injuries, including broken ribs.”

“That’s true,” Morgan said. “But the man was having a heart attack in the Guggenheim. I’m trained, of course, and I started C.P.R., but his heart wouldn’t start. I had to give him a pulmonary thump, you know, when you punch down on the ribcage to shock the heart? But it didn’t work. I tried it twice, and then the third time I had to really lean on him with both hands, and it worked. Yes, I broke his rib, but he lived. And then he files charges against me!”

“You’re kidding,” Ms. Stanley said.

“Here is the police report,” Morgan said, and produced a file folder from her briefcase. “And here is the judgment of the court, dismissing the charges.”

So you have another rising action (complication) and another periepeteia (reversal of fortune). And this can go on for as long as you decide the story requires.

I’ll give you another example, this one with more activity (notice I did not use the term ‘action.’ There is a difference between ‘action’ and ‘activity,’ a very big difference, it turns out, but more on that later.)

Supposing Buster K.’s wife is expecting her baby, and Buster is a nervous wreck. He’s not very well organized to begin with, and he’s especially inept under pressure. Worse, a storm dumped a foot of snow on the ground overnight, and is continuing. He was expecting the delivery in a week or two, but his wife tells him it’s happening today, right now, and he needs to get her to the hospital:

“Now?” he says. “But the storm?”

“There’s a storm going on in my belly,” she says quietly. “We have to move, Buster.”

He loads her into the car and lifts the garage door and pulls the car into the road, hearing the tires crushing through the snow and ice, and turns at the crossroads to take the bridge into town. But, there are electrical wires down and police barricades blocking the entrance: the bridge is out. First obstacle/complication.

So, you have a character with a desire (get honey to the hospital), a built-in raising of the stakes (premature labor plus the storm), and now a complication (the bridge is out). This is your rising action. But we’re not done, that’s too easy, because certainly there is an alternate route to the hospital, right?

Yes, but only one, and it’s up the mountain through the switchbacks, the most treacherous landscape for miles. What choice does he have? He turns the car and drives toward the mountain. And by now you can fill in the rest: half-way up he starts backsliding on the ice, goes off the road and hits a tree and blows a tire. There’s no spare in the trunk, he forgot to get it fixed the last time around, and he’s also out of gas.

The obstacles keep piling up, as do the stakes, the tension, the suspense, and I’m afraid that what you’ve got here is a page-turner. The stories at the end of this chapter (Jack London’s “To Build a Fire” and James Joyce’s “Araby”) are exemplary stories for the rising action (and everything else concerning conflict-crisis-resolution).

4. Climax:

When you have raised the stakes, tension, and suspense sufficiently for your means, it is time to present the Climax or Crisis Moment, the moment of truth, the point of no return. How to describe this? Well, let’s say you’re blowing up a balloon, and you’ve got it pretty well pumped up, and you know that with the next breath (or the one after) it will pop, so you’d better tie a knot in the thing and put it aside for the birthday party. Or, you’ve put a tea kettle on the stove, the whistling kind, and the water begins to boil, you can hear it bubbling in there, and you know at any moment it will begin that irritating high-pitched whistle that drives you nuts. That’s it, that’s the Crisis Moment, the moment of truth, the point of no return. Why do we call it a ‘moment of truth’ or ‘point of no return?’ Because this is the moment when your protagonist is backed against the wall and has to make a Choice.

Let me repeat that:

She has to make a choice.

I’m sorry, forgive me, but there is no way to over-sell this point:

At the crisis moment in the story, your protagonist must make a choice.

Because if your protagonist doesn’t make a choice, then she is a passive character, and we’re back to what we did over the weekend. Your reader wants, needs, demands a protagonist who is strong enough to take an active role in her life and, when push comes to shove, strong enough to make a choice. Whether it turns out well or badly, it doesn’t matter, we will have seen her in difficult straits, responding as best she can, and making a difficult choice that will change things forever. (Come on, now, if the choice is vanilla or chocolate at the ice cream parlor, then it’s not going to change much in her life.) This choice must be a significant choice, something that will change your protagonist in one way or another. Forever.

5. Falling Action:

As there was with the Rising Action, there is another “C” word that accompanies the Falling Action: Consequences. When your protagonist was backed to the wall, she had to make a choice, and that choice carried consequences. We expect our heroes to be strong enough to make these difficult choices, and brave enough to live with the consequences, be they happy (comedy) or sad (tragedy).

6. Resolution (Dénouement):

What happens? In literature, as in life, the characters go on living. But although the characters go on living, for the reader the story has to end.