8:24am: A Pillor of the Community

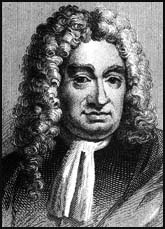

Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe is an interesting story; he didn't begin writing fiction until he was sixty years old, having previously confined his output to (hilarious) political satire. Robinson Crusoe, Defoe's story of a shipwrecked sailor and the native, Friday, whose life he saves, is a richly detailed and universal story of survival and redemption, not to mention a complete camping reference manual. It's a good thing Defoe turned his efforts to fiction, because his political satire got him in some hot water:

On July 31, 1703: Daniel Defoe is put in the pillory:

(From The History Channel) "On this day, Daniel Defoe is put in the pillory as punishment for seditious libel, brought about by the publication of a politically satirical pamphlet.

Defoe's middle-class father had hoped Defoe would enter the ministry, but Defoe decided to become a merchant instead. After he went bankrupt in 1692, he turned to political pamphleteering to support himself. A deft writer, Defoe's pamphlets were highly effective in moving readers. His pamphlet The Shortest Way with Dissenters was an attack on High Churchman, satirically written as if from the High Church point of view but extending their arguments to the point of foolishness. Both sides of the dispute, Dissenters and High Church alike, took the pamphlet seriously, and both sides were outraged to learn it was a hoax. Defoe was arrested for seditious libel in May 1703. While awaiting his punishment, he wrote the spirited "Hymn to the Pillory." The public sympathized with Defoe and threw flowers, instead of the customary rocks, at him while he stood in the pillory.

He was sent back to Newgate Prison, from which Robert Harley, the future Earl of Oxford, obtained his release. Harley hired Defoe as a political writer and spy. To this end, Defoe set up the Review, which he edited and wrote from 1704 to 1713. It wasn't until he was nearly 60 that he began writing fiction. In 1719, The Life and Strange Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, Defoe's fictional account of a shipwrecked sailor who spent 28 years on a desert island, was published. His other works include Moll Flanders (1722) and Roxana (1724). He died in London in 1731."

9:40pm: Field No. 2

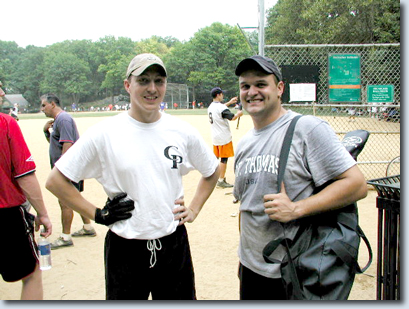

Paulo & Rod-Man

Sorry I haven't posted anything in a week, but I've been busy with a new book. Of course, the last one is yet unfinished, but an idea struck me, and if there's one thing I've learned about fiction it's to strike while the iron is hot. So, I plugged in my Sunbeam and pummelled it about the apartment for a while, and then set about the business of the book, and have been busy working on it lo these many days. But, there's a light at the end of the tunnel, it's called the weekend, and this weekend it consisted of softball, a triple-header on Sunday at Hecksher, Fields No. 2 & 4. Rod-Man joined me for the late games on field 4 and we had a great time on the sun-blanched diamonds of Central Park, with kids frolicking in the playground nearby, the local footmeisters playing soccer on the little league-sized field No. 1, and a bunch of locals and tourists sitting in the bleachers watching our game, including this poor, sweet old guy sitting in the third row with his nephew. It was during batting practice before the 3rd game, I was on deck, just acting as backstop to return unhit balls to the pitcher, and the batter fouled a ball into the bleachers. I yelled "heads up" and this old guy in the white suit didn't look, didn't duck, he just dove for cover, taking a nose-dive off the edge of the bleachers and face-first into the dirt. Jesus, I'm thinking this guy was brainwashed by Frankenheimer's Manchurians in WWII and "heads up" was his signal code; it was like I activated this guy and he was back in the trenches in Okinawa or something! So I immediately ran over to this guy, he was 75 if he was a day, and he was pretty well shaken up. I helped him up and he was checking all the moving parts, and to my great surprise and relief it seemed like everything was still connected. I gently explained to him that "heads-up" means cover your head or something, don't take a swan dive off the high board.

Meantime, this same batter is still taking his swings, and I told him he now had reckless endangerment, possession of a low batting average, and harrassment of a war veteran on his rap sheet. This, however, proved to be no deterrant, as two pitches later he fouled off another ball, this one straight up behind the backstop where people were walking, two Asian women included, and right in the path of this falling missile. "Heads up," I yelled again (like it did me any good the first time) and luckily they did not put their "heads up," because the ball glanced off the top-front of one of them, and if she had looked up at that moment (as I'd unwisely advised her to) the rest of her Sunday afternoon would likely have occurred in the emergency room.

I looked at the kid in the batter's box. "Well, that's failure to put the ball in play, failure to yield to the Mendoza Line, and bodily assault with a badly batted ball," I told him. "And by the way: strike two."

I am by this time seriously debating the use of that phrase as a warning signal, considering the adoption of something less directive, like "the sky is falling" or something. Of course, there is the fowl possibility of acquiring another derogatory nickname but, oh well.

And it didn't end there, either. Must be there's gonna be a full moon tonight, because in the bottom of the fourth, just as I was stepping into the batter's box, another guy rode by on his new mountain-bike, tried to pull to a stop, and crash-landed in a heap behind the backstop. I ran over to him to see if he was all right, and he had some scrapes and bruises, and a little gash on his left knee, but again all the moving parts seemed to be functioning. Seems he was unused to the stirrups on his pedals, and I have to admit my own give me fits if I try to stop to quickly and am slow to pull my foot out of the damned thing, and it's cost me a tire on at least one occasion, and just last week at that, but that's another story.

So anyway, we're playing our game, and along about the bottom of the fifth I'm running after a long fly ball to deep right field and nearly crash into the left fielder from Field No. 2, as the Hecksher fields overlap in the outfield and always have and always will, so the outfielders are dancing between the raindrops to get a bead on their own popups and stay out of the way of the other guy's, and so forth. Well, after the play I turn to thank the guy for clearing the way and find it is none other than Paulo, a teammate of Rod's and mine on our Mo's Amigos softball and It's On, Old No. 7, Brother Jimmy's and Mo's Giants football teams. Yikes! It's a small world (but I wouldn't want to paint it). So after the game Rod-Man and I walked by Diamond 2 and said hello to Paulo (whence the photo above) and that was a nice little spontaneous confluence of the planets, and all right here on our own little postage stamp of America. It's called Central Park; and by the way, it's real, and it's spectacular.

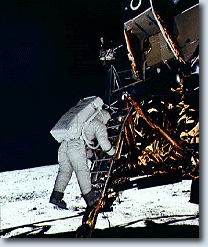

12:59am: "The Eagle Has Landed"

July 20, 1969:

Neil Armstrong steps onto the moon

(From The History Channel) "At 10:56 p.m. EDT, American astronaut Neil Armstrong, 240,000 miles from Earth, speaks these words to more than a billion people listening at home: "That's one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind." A moment later, he stepped off the lunar landing module Eagle and became the first human to walk on the surface of the moon.

The American effort to send astronauts to the moon has its origins in a famous appeal President John F. Kennedy made to a special joint session of Congress on May 25, 1961: "I believe this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth." At the time, the United States was still trailing the Soviet Union in space developments, and Cold War-era America welcomed Kennedy's bold proposal.

In 1966, after five years of work by an international team of scientists and engineers, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) conducted the first unmanned Apollo mission, testing the structural integrity of the proposed launch vehicle and spacecraft combination. Then, on January 27, 1967, tragedy struck at Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Florida, when a fire broke out during a manned launch-pad test of the Apollo spacecraft and Saturn rocket. Three astronauts were killed in the fire.

Despite the setback, NASA and its thousands of employees forged ahead, and in October 1968, Apollo 7, the first manned Apollo mission, orbited Earth and successfully tested many of the sophisticated systems needed to conduct a moon journey and landing. In December of the same year, Apollo 8 took three astronauts to the dark side of the moon and back, and in March 1969 Apollo 9 tested the lunar module for the first time while in Earth orbit. Then in May, the three astronauts of Apollo 10 took the first complete Apollo spacecraft around the moon in a dry run for the scheduled July landing mission.

At 9:32 a.m. on July 16, with the world watching, Apollo 11 took off from Kennedy Space Center with astronauts Neil Armstrong, Edwin Aldrin Jr., and Michael Collins aboard. Armstrong, a 38-year-old civilian research pilot, was the commander of the mission. After traveling 240,000 miles in 76 hours, Apollo 11 entered into a lunar orbit on July 19. The next day, at 1:46 p.m., the lunar module Eagle, manned by Armstrong and Aldrin, separated from the command module, where Collins remained. Two hours later, the Eagle began its descent to the lunar surface, and at 4:18 p.m. the craft touched down on the southwestern edge of the Sea of Tranquility. Armstrong immediately radioed to Mission Control in Houston, Texas, a famous message: "The Eagle has landed."

At 10:39 p.m., five hours ahead of the original schedule, Armstrong opened the hatch of the lunar module. As he made his way down the lunar module's ladder, a television camera attached to the craft recorded his progress and beamed the signal back to Earth, where hundreds of millions watched in great anticipation. At 10:56 p.m., Armstrong spoke his famous quote, which he later contended was slightly garbled by his microphone and meant to be "that's one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind." He then planted his left foot on the gray, powdery surface, took a cautious step forward, and humanity had walked on the moon.

"Buzz" Aldrin joined him on the moon's surface at 11:11 p.m., and together they took photographs of the terrain, planted a U.S. flag, ran a few simple scientific tests, and spoke with President Richard M. Nixon via Houston. By 1:11 a.m. on July 21, both astronauts were back in the lunar module and the hatch was closed. The two men slept that night on the surface of the moon, and at 1:54 p.m. the Eagle began its ascent back to the command module. Among the items left on the surface of the moon was a plaque that read: "Here men from the planet Earth first set foot on the moon--July 1969 A.D--We came in peace for all mankind."

At 5:35 p.m., Armstrong and Aldrin successfully docked and rejoined Collins, and at 12:56 a.m. on July 22 Apollo 11 began its journey home, safely splashing down in the Pacific Ocean at 12:51 p.m. on July 24.

There would be five more successful lunar landing missions, and one unplanned lunar swing-by, Apollo 13. The last men to walk on the moon, astronauts Eugene Cernan and Harrison Schmitt of the Apollo 17 mission, left the lunar surface on December 14, 1972. The Apollo program was a costly and labor intensive endeavor, involving an estimated 400,000 engineers, technicians, and scientists, and costing $24 billion (close to $100 billion in today's dollars). The expense was justified by Kennedy's 1961 mandate to beat the Soviets to the moon, and after the feat was accomplished ongoing missions lost their viability."

Past Midnite: A New Publication

Nice birthday present for yours truly, this book arrived in the mail this afternoon, a copy of the new issue of RiverSedge, a literary journal published by the University of Texas-Pan American Press. Libby's Foot is a short little story, 1,500 words, and was originally published in 1999 or so in Nebo. Here's the story in case you feel like reading:

Copyright 2002 G.D. Peters

LIBBY'S FOOT

by

G.D. PETERS

Libby's foot protrudes tranquilly from beneath lace-edged covers printed with lilacs and roses, a slender, delicate organ which perfectly represents the rest of her, lying quiet as a mist of spring rain in the twilight of early dawn. The toenails are painted a deep blood-red, fastidiously groomed with great care and precision in a hue which rivals the crimson lip gloss she wears when she is making love. The toes are soft and elegant, devoid of barnacles and calluses which mar the feet of the most beautiful of women. But Libby has been kind to her feet, sparing them the torturous cramming and stuffing into tight-fitting pumps and heels which is so common among those who have been less vigilant with their physical well-being. In this matter, at least, Libby has not been careless.

The top sheet slopes away evenly, defining with its gentle curve the lovely shape of a milk-white calf, the well-proportioned fullness of her leg, one knee drawn into a half-fetal crook which accents the comely shape of her bottom.

At Libby's waist the sheets are gathered in a series of tight folds where her left fist clutches firmly to the smooth linen, pulling an irregular panel taut in a crisp shroud which catches at the base of her elbow. Her fingers are graceful and pretty, the nails well-manicured, painstakingly polished with the same enamel which graces the toes. As petite as is the hand, the grip which it maintains on this section of fabric is deceptively strong; one can see a taut contraction of carpal tendons beneath the cream-smooth skin. There is a noticeable tan line on the finger where a wedding ring is usually worn.

Down on the avenue a milk truck grinds to a halt, its hydraulics gasping and spitting as it eases two tons of white cargo to the curb. The driver holds a clipboard, noting the time and date. He will rest while the crates are unloaded, his role fulfilled once delivery has been made.

On the dresser against the wall is a wedding picture, matted and framed with loving care and proper regard to symmetry and balance. The matting matches the hand-embroidered antiquity of Libby's dress, the ebony frame the crisp elegance of the groom's tuxedo. The photograph shows a laughing Libby, holding aside her veil with a free hand, her mouth open, prepared to accept a traditional offering from the grand wedding cake.

As morning light begins to filter through drawn shades it is possible to discern the outline of Libby's clothing, which has been haphazardly discarded, piece by piece it would appear, on the wine- colored, braided oval rug beside the bed. A skirt lies close upon the footpost, its pleats uncharacteristically disarrayed and rumpled. Libby spotted the skirt in a small boutique last winter while vacationing in the Caribbean and asked if she could buy it. She needn't have asked; when have I ever denied her anything she might have wanted? Her white cotton panties lie at an odd angle at the foot of the night stand, rolled into the shape of a figure eight, the mathematical symbol for infinity, the way ladies' panties become when they are hastily removed.

The time changes on the old dinosaur of a clock Libby keeps on the night stand, a pre-digital remnant from her college days whose hinged panels flip down like Rolodex cards to reveal a new top and matching bottom; it is no longer 4:57, the top half of the "7" having swiveled to reveal an "8." Although it is outdated, this early electronic relic has proved steadfast and reliable, two admirable qualities, even in a clock. Certainly they are desirable in a person, especially if one loves her and has pledged to her one's lifelong devotion.

Out on the avenue milk crates roll from the cargo hold down stainless track rollers to the sidewalk, there to be caught and stacked by a grocery clerk. A fire engine turns the corner coming off the avenue, the unique purr of its motor unmistakable even at a distance, and begins to slow as it nears the firehouse, its air brakes audible as a series of sighs. The warning beep sounds thinly through the early morning quiet, meep...meep, serving ample notice for all to stand clear as 44 Engine backs into its hangar. It is almost as though this tone echoes through the room.

From a vantage point at the foot of the bed one can view the silhouetted outline of Libby's graceful figure as a bas-relief of lulls and rises ebbing and swelling beneath the top sheet. In this position, with one leg raised and the other extended to a length, her torso bent slightly at the waist in a runner's crouch, Libby resembles the sprinter streaking toward the finish line, this taut section of linen the ribbon she will break the moment the line is crossed.

As daylight slowly invades the shadowy realm of twilight, one is able to see the area surrounding the bed. On the floor to the right an overturned wine bottle reclines, the remainder of its contents seeped well into the Persian rug which covers the open area of the floor, a red stain soiling the earthen beauty of this charming artifact. One half-empty stem glass stands beside the clock atop the night table on Libby's side of the bed. Another, on the other side, has been broken amid some confusion, its jagged shards scattered on the floor beneath the window. On this side, as well, are more discarded clothes: a pair of trousers, one leg balled beneath the rumpled heap, the other extended toward the bed. A long-sleeve shirt is there as well, but one sleeve has been removed; it lies there disfigured, no longer able to serve the purpose for which it was created.

Above the point where Libby's elbow catches the edge of the sheet it falls away in a series of loose waves toward the headboard, a fine antique of hand-carved oak symbolically representing the cycle of life in its depiction of the lunar phases: crescent-, quarter-, half- and full moons, beautifully crafted and side by side.

A new driver is being trained at the helm of 44 Engine, his persistent attempts to dock the craft audible as a series of engine heaves and warning tones as the great vessel is backed repeatedly through the threshold, whose brick facing is painted the traditional bright red, its open bay inviting the union with brass and steel and two hundred feet of fire hose.

Another panel flips on Libby's clock, mechanically illustrating the passing of a limitless series of moments with a single gesture representing one finite number. Only for one instant, infinitely shorter, actually, than a nanosecond, was it truly 4:59. The panel will remain unchanged, however, while time presses onward, ever streaking across the firmament toward Armageddon, infinite and eternal.

If only the earthly condition would remain so constant, how much simpler life would become. As it is, however, this life is not very simple at all, it is a complex fusion of hopes and fears, of promises and desires, a twisted mass of give and take and borrow and steal, gnarled and bony, rooted only in self-gratification and fueled by the instinct for survival. In the face of this, one's heart stands helpless against the armament of unforgiving love.

Thus, when the battle is waged and the challenge thrown down, one can only run for cover or take up the gauntlet and engage the grave disease. One choice is for the cowardly, the second a simple reflex in the quest for self-preservation. I have only myself to blame for my predicament, and will surely be in some trouble when this is done.

The outline of Libby's ample breast can be seen pressing up from beneath the sheet, which falls in a loose fold across her bare shoulder. That is all that is left of Libby here on the bed. There is a stain at the top of the sheet, spreading like ink drops in water at the end of her neck where her pretty head, which now is gone, once rested. The head now is over here, in this corner, on the lap of Edgardo where I have placed it. Edgardo's eyes are wild with fright above the gag which I have tied about his head, fashioned from the sleeve of his shirt, to keep him silent while I work. He sits wriggling in the chair, naked (as I found him), arms and legs bound tightly and Libby's severed head upon his lap, worrying, too late now, over what I am about to do.

THE END

Hope you liked it; you can read the rest of my published work on my Fiction Page.

1:24pm: Plus, A Famous Duel

The Running of the Bulls:

From Reuters: "A fighting bull with a shirt hanging on its right horn slips on the wet streets as it charges through central Pamplona during the first run of the week long San Fermin Festival on July 7, 2002. The photo prompted numerous inquiries about the fate of photographer Desmond Boylan, but he said that he was safely out of harm's way behind a barrier, using a remote to fire the camera which was wrapped in wads of bubble wrap leaving just the lens poking out." Photo by Desmond Boylan/Reuters

And this: On this date in 1804 U.S. Vice President Aaron Burr fatally shot former Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton in an "affair of honor" (duel).

From The History Channel: "In a duel held in Weehawken, New Jersey, Vice President Aaron Burr fatally shoots his long-time political antagonist Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton, a leading Federalist and the chief architect of America's political economy, died the following day.

Alexander Hamilton, born on the Caribbean island of Nevis in 1757, came to the American colonies in 1773 as a poor immigrant. In 1776, he joined the Continental Army in the American Revolution, and his relentless energy and remarkable intelligence brought him to the attention of General George Washington...

...who took him on as an aid. Ten years later, Hamilton served as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention, and he led the fight to win ratification of the final document, which created the kind of strong, centralized government that he favored. In 1789, he was appointed the first secretary of the treasury by President Washington, and during the next six years he crafted a sophisticated monetary policy that saved the young U.S. government from collapse. With the emergence of political parties, Hamilton was regarded as a leader of the Federalists.

Aaron Burr, born into a prestigious New Jersey family in 1756, was also intellectually gifted, and he graduated from the College of New Jersey (later Princeton) at the age of 17. He joined the Continental Army in 1775 and distinguished himself during the Patriot attack on Quebec. A masterful politician, he was elected to the New State Assembly in 1783 and later served as state attorney. In 1790, he defeated Alexander Hamilton's father-in-law in a race for the U.S. Senate.

Hamilton came to detest Burr, whom he regarded as a dangerous opportunist, and he often spoke ill of him. When Burr ran for the vice presidency in 1796 on Thomas Jefferson's Democratic-Republican ticket (the forerunner of the Democratic Party), Hamilton launched a series of public attacks against Burr, stating, "I feel it is a religious duty to oppose his career." John Adams won the presidency, and in 1797 Burr left the Senate and returned to the New York Assembly.

In 1800, Jefferson chose Burr again as his running mate. Burr aided the Democratic-Republican ticket by publishing a confidential document that Hamilton had written criticizing his fellow Federalist President John Adams. This caused a rift in the Federalists and helped Jefferson and Burr win the election with 73 electoral votes each.

Under the electoral procedure then prevailing, president and vice president were not voted for separately; the candidate who received the most votes was elected president, and the second in line, vice president. The vote then went to the House of Representatives. What at first seemed but an electoral technicality--handing Jefferson victory over his running mate--developed into a major constitutional crisis when Federalists in the lame-duck Congress threw their support behind Burr. After a remarkable 35 tie votes, a small group of Federalists changed sides and voted in Jefferson's favor. Alexander Hamilton, who had supported Jefferson as the lesser of two evils, was instrumental in breaking the deadlock.

Burr became vice president, but Jefferson grew apart from him, and he did not support Burr's renomination to a second term in 1804. That year, a faction of New York Federalists, who had found their fortunes drastically diminished after the ascendance of Jefferson, sought to enlist the disgruntled Burr into their party and elect him governor. Hamilton campaigned against Burr with great fervor, and Burr lost the Federalist nomination and then, running as an independent for governor, the election. In the campaign, Burr's character was savagely attacked by Hamilton and others, and after the election he resolved to restore his reputation by challenging Hamilton to a duel, or an "affair of honor," as they were known.

Affairs of honor were commonplace in America at the time, and the complex rules governing them usually led to an honorable resolution before any actual firing of weapons. In fact, the outspoken Hamilton had been involved in several affairs of honor in his life, and he had resolved most of them peaceably. No such recourse was found with Burr, however, and on July 11, 1804, the enemies met at 7 a.m. at the dueling grounds near Weehawken, New Jersey. It was the same spot where Hamilton's son had died defending his father's honor two years before.

There are conflicting accounts of what happened next. According to Hamilton's "second"--his assistant and witness in the duel--Hamilton decided the duel was morally wrong and deliberately fired into the air. Burr's second claimed that Hamilton fired at Burr and missed. What happened next is agreed upon: Burr shot Hamilton in the stomach, and the bullet lodged next to his spine. Hamilton was taken back to New York, and he died the next afternoon.

Few affairs of honor actually resulted in deaths, and the nation was outraged by the killing of a man as eminent as Alexander Hamilton. Charged with murder in New York and New Jersey, Burr, still vice president, returned to Washington, D.C., where he finished his term immune from prosecution.

In 1805, Burr, thoroughly discredited, concocted a plot with James Wilkinson, commander-in-chief of the U.S. Army, to seize the Louisiana Territory and establish an independent empire, which Burr, presumably, would lead. He contacted the British government and unsuccessfully pleaded for assistance in the scheme. Later, when border trouble with Spanish Mexico heated up, Burr and Wilkinson conspired to seize territory in Spanish America for the same purpose.

In the fall of 1806, Burr led a group of well-armed colonists toward New Orleans, prompting an immediate U.S. investigation. General Wilkinson, in an effort to save himself, turned against Burr and sent dispatches to Washington accusing Burr of treason. In February 1807, Burr was arrested in Louisiana for treason and sent to Virginia to be tried in a U.S. court. In September, he was acquitted on a technicality. Nevertheless, public opinion condemned him as a traitor, and he fled to Europe. He later returned to private life in New York, the murder charges against him forgotten. He died in 1836."

3:56am: Published in Prairie Winds

My short story "Knowledge and Illusion" was published this week in Prairie Winds, a literary journal published by Dakota Wesleyan University. The Journal looks like this:

Read "Knowledge and Illusion" on G.D.'s Fiction Page

And here is the story if you feel like reading:

© 2002 G.D. Peters

KNOWLEDGE AND ILLUSION

by

G.D. PETERS

Somewhere among the vast, uncharted landscape of the human anatomy is a gland so small it can not be found with lance and probe, surgeon or scalpel, but which houses the thinnest of fibers, a single nerve that is the sensor for all that is unseen, unspoken, unheard in the small, rich circle of one’s circumstance and experience. This sensor acts as a filter, sifting the truth from what is true. And since everything that exists, by its very act of being, exists in a state of truth, whether tautology or falsehood, fact or fabrication, one thing for certain that can be known is that nothing can be known for certain. Everything, including knowledge, exists in its own state of illusion. Knowledge, therefore, is itself an illusion, a false and fleeting state of grace, supported by its greatest weakness—fallibility—and bolstered by its own, forever shifting, maze of mirrors. The frayed, haphazard edges of knowledge and illusion wreak a constant havoc on the frailty of the human condition.

Wilfredo Herodotus Boschetti, Knowledge and Illusion, 1759

"Pray look better, Sir…those things yonder are no giants, but windmills."

Miguel de Cervantes, Don Quixote, 1605

*

Adriénne stands beneath a threatening gray sky, fingering the handle of an oversized valise and shifting her weight uneasily. From the corner of one eye she spies a movement, turns her head to see an inchworm gyrating frantically at the end of a slender thread. Her bearing shifts imperceptibly as she traces the silk ribbon to its source just above her, beneath a limb of the mulberry tree overhanging the sidewalk in front of Richard’s apartment.

“What should you likes me to do?” she says to Richard, nervously eyeing the worm.

Richard stands motionless, arms crossed and lips locked in a stoic grimace, as Adriénne wipes tears from her face with a crumpled tissue, leaving smudged rivulets trailing her cheeks which, a month earlier, he would have lovingly cleansed with pursed lips. Now he remains unmoved and unmoving, unable to formulate an answer.

“I don’t know,” he finally manages, looking up to find her eyes upon him, narrowed and hostile. “What do you want?”

Adriénne watches the worm drop several inches and abruptly stop, twisting at the end of its silk. She is about to respond but, thinking better of it, remains silent.

When the two of them moved in they were like newlyweds. I was sitting here on the terrace (my fire escape), smoking a little cigar and watching as they unloaded the van and trundled their belongings to the third-floor rear, just up the steps from my own little flat. Him I instantly made for a New Yorker, not once did he look up to catch a new neighbor taking his leisure of an autumn afternoon. She, on the other hand, had looked not once but several times, and we had, in some secretive fashion, exchanged waves and covert glances. She made a game of not telling him I was there, waiting to see if he would look for himself. But I knew what she did not, that we New Yorkers never look up. And, he never did.

Anyway, you might have thought they were the happiest couple anywhere. I would have thought so myself if Vanessa and I had not actually been the happiest couple anywhere. But as there must be an upper limit placed on absolutes it was necessary to apportion some hierarchy to our relative states of beatitude, so I agreeably graded them down a step on the scale of infinite bliss, trusting they would find contentment in mediocrity.

As I watched these lovebirds carefully constructing their nest with bits of twigs and grass it occurred to me that perhaps a like fortune might soon grace my own peasant lot. And, coincidentally, in the midst of this fancy (as if precisely on cue) the enchanting figure of Vanessa appeared, coming toward me on the sidewalk down the block. Watching her walk was one of my greatest pleasures, as she had a childlike bounce to her step which never failed to captivate me. And though she had been living in New York several years she retained her outsider’s idle curiosity, looking up as often as the greenest tourist off the boat. She did so even at this moment, spotting me on the fire escape and waving as she came (and I had only time enough to jump through the window and brush the taste of tobacco from my teeth before the buzzer rang and she was at my doorstep).

“Hiiii,” she smiled, stepping across the threshold and into my arms and a warm kiss. “Oh, so you do miss me,” she teased when I offered her a moment’s breath.

“What, me?” I joked. “Hell, I’m just trying to make a homely girl happy.”

“Ohhh,” she said. “See? And it worked!” She lowered her purse as I helped her out of her sweater.

“Can I take your blouse?” I said.

“Oh, new material!”

“Hey, I’m syndicated.”

“No wonder, you’re hilarious!” she said as, from outside my door, we heard the sound of something large being bounced and hoisted up the steps. “New neighbors?”

“Yeah, newlyweds, I think,” I said. “Imagine, we could have had a double wedding.”

“Ahh,” she narrowed her eyes, “always the jokester.”

Like this.

We sat together on the sofa and listened to music, patching together the fabric of our covenant with soft lies and dirty kisses, all the while hearing the lifting and jouncing of our newlyweds’ chattel being pushed and lugged and dragged and driven to roost.

But I saw it coming, their trouble in paradise. Not right away, it’s true, but from a fair enough distance, and clear as a dark cloud shouldering its way through the warm tranquility of a perfect sky. In the beginning, though, we would hear them bouncing down the steps, laughing and talking, generally enjoying the hell out of their new life together on the upper west side. One time we heard them come halfway down the steps and stop. Vanessa pulled her lips from mine.

“What happened?” she asked.

“Does my funny looking head now resemble a crystal ball?”

“Ohhh, always the prankster.”

“Well, don’t let me stop you,” I said, “I know you’re dying to look through the creep-hole.”

She furrowed a brow, but rose nonetheless and tiptoed furtively toward the door. In a moment she was back beside me, a conspiratorial smile on her face.

“They’re kissing in the hallway,” she whispered.

“What!” I gasped in mock rage and indignation. “Right now? Here, before our very noses! What of the tabloids, the internet? A scandal in our midst; oh, the horror…”

Vanessa pushed me away, then reached her arms around my neck and pulled me back for another wave of kisses which I guzzled as the elixir of life itself. For our lovebirds upstairs, however, the climate was not long in changing. Of course Adriénne did not have the benefit of my perspective, but I am loathe to poke my nose where it does not belong, and here it did not. I therefore kept my own counsel and trusted that, like water seeking its own level, their union would settle in its proper place. Still, I was not blinded by my reticence, nor prevented from witnessing (simply because, like the referee in a prize fight, I was literally atop the action) every nuance of deception that crept its way into the lives of these good people. The first blow came late one evening as I returned home from work. I heard someone on the stairwell and turned to find Adriénne sitting at the top of the stairs, rocking herself as she wept into a pair of praying hands.

I reached out with a simple utterance of her name. “Adriénne?”

She started at this, looking down, and choked on her reply, struggling for composure.

“What’s wrong?” I asked, placing a foot on the first step in what I intended as an overture of solace. Her lovely blue eyes were puffed with worry and bloodshot-red, and I felt a pang of guilt affecting naiveté as I did, for two nights earlier I’d seen Richard down the block, his arms draped intimately about the waist of another woman. I did not know if anything had happened between him and Adriénne, it was none of my business if it had. Yet there I stood feigning ignorance, and the longer I did so the greater, evidently, the strain on her resistance, for she finally burst into great spasms of tears, and once the dam broke it was no longer possible, merely with upraised foot, to hold forth some vague notion of comfort. I quickly climbed the steps, half-worried that Richard himself might appear on the landing (while at the same time practically hoping he would). I sat beside her and drew her close, caressing quivering shoulders, her rain of tears wetting my sleeve. I didn’t speak, but merely waited, and when the fever had run its course she released a torrent of emotions.

“I don’t know what is wrong. This is something with Richard, but she says no, nothing is wrong.”

“Did something happen?” I asked.

“Yes, must be something is happen. She says no, but I know something is happen. I should like to ask but she says this is nothing. But hey, I am staying with Richard every long times, and knowing if something it’s little bit change like this, or little bit like this. So she is working late and…every night late, you know, coming late to work, and I should like to say why, and she tells to me listen, it is just working, you know. But I know is not just working, I mean we are spending two years in Czech Republic and Richard is working equal jobs, and never something to happens like this, you know, not in two years.”

I was unable to offer any consolation, especially considering I was privy to Richard’s infidelities. I therefore held my tongue, pulled more firmly on her shoulder, and hoped that this would provide some comfort.

“I don’t know what to do,” she continued, “I should like to talks to him but she doesn’t want to talks. Meantime I am coming to States, to New York City, yeah? But at home I am study in one of best universities, you know, but I am giving up university. Sure, Richard says, hey, come to New York to lives with me, so I should like to be with him, yeah, so I am leaving university and come to New York, and I haff no friends, and now I haff no Richard, too.” She continued to rock, pushing aside tears with her fingers.

“Well,” I said, “but you have a job; must be you have some friends there?”

“Yes, but is only hostess jobs at little restaurant, and those waitress, they never talks to me, always.”

As I held Adriénne I realized this was the first real conversation I’d had with her, our prior contact consisting in hand waves, smiles, and brief hellos in the hallway. To me she had always been the beautiful young foreigner, her blond hair and tall, voluptuous figure tantalizing even for a man so firmly in the throes of love. I was finding now that behind the elegant, mysterious European was simply a sweet kid with an accent who got yanked in over her head. When I kissed her on the cheek and said good-night, offering empty, if optimistic, assurances, I found myself looking into the eyes of a child: frightened, lonely, and a long way from home. But there was nothing I could do about the inevitable heartache that, even now, was measuring its tender target.

“Hey, I am crying all this time and not even to say sorry to you,” Adriénne said, a hand on the doorknob, her face turned over one shoulder.

“To me?” I asked, turning from the stairwell.

“You are not breaking up with girlfriend, too? I mean, because I am seeing her today on street, I should like to say hello but…”

Here she abruptly stopped.

“Oh,” I said. “The other man?”

She nodded gravely.

“It’s complicated,” I said, nodding my own head as if I understood what I was talking about, which I did not, although I knew it the way one knows the taste inside one’s mouth. I sank to the depths of my own apartment uncertain whether, for all my trouble, I had done any good, and feeling, rather, as if I’d simply grappled the great boulder from Adriénne’s shoulder and hefted it onto my own. Adriénne’s life was beginning to unravel before her eyes (or, at any rate, mine) and I was left pondering not only her precarious future, and the vulnerable innocence of a stricken heart, but also the muddled state of my own affairs, for Vanessa had seemingly arrived at a crossroads, and I was worried about which path she would choose.

The truth of the matter is that Vanessa was a married woman. As for our being the happiest couple anywhere, this was an illusion, a maze of mirrors turning back on itself in rapid revolutions, throwing off a blinding light. Adriénne had seen Vanessa walking with her husband through the neighborhood. (I have had the same misfortune more than once.) It’s true they are married, and living together in what I presume is a tidy apartment here in our pleasant community. I did not perpetrate our lie to appease some twisted appetite for intrigue, but because my love was stronger than my conscience. As I am the villain in this, I do not renounce my complicity, but plead instead the tenacity of love’s embrace, no feeble grasp but vice-like, and formidable. That one becomes despicable under its spell is beyond one’s control.

Who knows how these things happen; you certainly don’t plan them. One minute you’re talking across the bar to a customer, a woman whose beauty seems crafted to your particular sensibilities. She flirts a little but freely confesses, when finally you have broken down and invited her for an afternoon in the park, that she is married. “Oh well,” you offer, graciously surrendering to reality, “so bring him along.” And that, you later learn, is the note which strikes a harmonious chord within the music of her lovely soul. She returns several times, and when once more you venture to extend an invitation, this time for a movie (“—we can be friends and watch a movie, right?” she posits), you have crossed a line you did not know was there and never saw. The next thing you know she is sitting beside you on the sofa three afternoons a week, and before you can prevent it the two of you have succumbed to the strongest of urges and fallen in love.

Well, but now there is the husband, and what began as an amorous tryst has developed into a full-scale love affair replete with the trappings of deceit, the sturm and drang—anxiety and guilt—that is inevitable when good and well-meaning people fall prey to temptations of the heart. And what of the unsuspecting husband? Even after two years Vanessa swore he didn’t have a clue. My own shortcomings aside, I couldn’t help but wonder at the nature of that guy’s illusions. I didn’t want to add to Vanessa’s already burgeoning stockpile of anxiety, but to be honest I was beginning to hope he would find out, to get it in the open and reach an honest resolution, if that word may be applied to this unhappy arrangement.

But I could tell Vanessa was nearing a turning point, soon to choose one path or the other, if a man can be considered a path. I was hoping Vanessa was secure in her love for me, convinced I could provide in richness for her soul what he could only flail at with doting devotion and a deep pocket. Tensions in her household were multiplying, edges frayed with innuendo and indifference, and more than once she had settled beside me on the sofa and sighed with exasperation “—I can’t take it anymore.” Yet time and again she faltered, lacking, perhaps, in conviction what she had of abundance in desire. Yet, believing the strongest dam would not forestall the mightiest flood, I patiently awaited the event that would enrich my life immeasurably.

Adriénne, in the meantime, had been undergoing a crisis of a different disorder. I saw her a week later, and this time it was not necessary to climb the steps to find her, for she was sitting at the foot of the stairs, crying in front of my apartment, and looking worse, if possible, than before.

“Hello,” I said, kneeling beside her.

“I am sorry to waiting for you,” she said through captured breaths, “but I has no one to talks to.”

“Do you want to come inside?” I offered, and she immediately rose, as I unlocked the door, and followed me in.

I draped my jacket over a chair and grabbed a shot glass and the bottle of Jack from the kitchen, pouring off a legal shot and handing it to Adriénne, who had quietly settled on the sofa.

“Here,” I said, preparing to explain its medicinal value, when she snatched it up and downed it. I poured another and she began, haltingly, and through a steady accompaniment of tears, to unburden herself.

“I don’t know what is wrong with me, maybe I am bad persons, but always I should trying to be good.”

I pulled a chair to the sofa and sat before her. She sipped at the shot and gathered herself with several deep sighs. “Today is worst day of life for me,” she went on. “I tolds to you I come to States from my home, I haff no friends here, no one to talks to me, and only jobs is hostess in small restaurant. And yesterday Richard is telling to send me home.”

“Home,” I said, “you mean back to Czechoslovakia?”

“To Czech Republic, yes.” She now downed the second shot as grief of a greater measure found its footing in her heart; she began trembling as if the temperature had dropped thirty degrees. “Now she likes to breaking up.”

“But why?” I asked, holding out the box of Kleenex, from which she gratefully plucked two blooms.

“I don’t know. I don’t know what is happen to me. But I am having to works tonight at restaurant, so I am thinking, okay, so I have jobs. I mean, we live in same apartment, but I don’t has to go home; with jobs I can find new apartment. But when I am coming to works…”

She began sobbing. I sat beside her on the sofa, once more offering an arm across her shoulders.

“When I am coming to works manager is telling to send me home,” she said.

“You mean you got fired?”

“Yes, and every time I am trying to learn better, but manager says I am one months at restaurant and not learning computer, not learning foods menu, and English not every good.”

I nodded my head.

“And I am borrowing money from cousin to come here, and ticket home is not before January. I am leaving best university to come to States, I don’t wants to go home no money for cousin and no jobs and no boyfriend, like run home to mother.”

“I understand.”

“But now I haff no stupid hostess jobs, how can find new apartment?”

“Hey,” I countered, trying to sound upbeat, “you are young and pretty, you can walk into any bar or restaurant and get a job. Are you kidding me, this is New York City, a beautiful girl like you, you’ll have a job before the end of the week, guaranteed.”

She was skeptical, but I had been in the city long enough to know this was true. Though her heart was breaking, there would be opportunities for one such as her. From her purely personal perspective, however, I understood that things were not quite looking up for Adriénne. She had given up everything for what seemed more than everything, the dream of a lifetime, only to wake up one morning (yesterday morning, actually) and find it all lying in pieces.

Well, I don’t blame myself for comforting a grief-stricken maiden in her time of crisis, but I can’t shake the feeling her spell passed to me the moment I reached out to her with open arms. How could I feel otherwise? I left her at the foot of the steps with a rigorous hug and best wishes for a bright outcome, and bolted my door with the condescending taste of pity on my palate, sorry for her plight but happy it had not befallen me.

On Monday I waited to hear from Vanessa, hoping she would be calling with good news about our future. I was troubled when she did not call, but not worried, although when I did not hear from her on Tuesday I began to feel unsettled. Still, I did not want to call her and cast the first stone over calm waters. On Wednesday, finally, she did call, and came to see me in the afternoon as if nothing had happened, or so I thought.

She sat beside me on the sofa, acting for the world as if nothing had changed, but there was something in her bearing that betrayed a deeper burden. It seemed she had news for me that was not exactly pleasant. It was late afternoon, and we listened as an autumn wind rattled the branches outside my window. Vanessa sat quietly, regarding me with something large trapped behind her dark eyes. I watched, fearful, as it struggled to break free, feeling its regret, sensing an impulse to shed its restraints and smother me with truth or illusion, whichever might hurt me least.

“I have something to tell you,” she began.

“It would appear.”

Our eyes embraced. “I’m moving,” she said.

Something shifted, then shifted again. And then fell.

“You’re moving, as in you are moving? Or you’re moving, as in you and he are moving?”

She hung her head. “I’m sorry,” she said.

Then everything that had been falling crashed with an inertia of finality. I looked below me and saw the ground spiraling away from far off in the distance, a vertigo twister which reeled off my guts in a suffocating vacuum of compromise and regret, while something inside my head seemed to watch from the top of a nearby cliff.

“I’ve been afraid to tell you for a month now.”

My face went flush, feeling the pricks of a million tiny pins. “Well,” I finally managed, “I don’t know why? Why should it matter to me if you’re living with him at this apartment or move with him to another?” I could not tell whether I had succeeded in masking my devastation.

“I don’t know,” she said, “it’s just that we talked about my leaving him.”

“Yes,” I said, “we did. But I would have thought that—after two years of this—if you were going to leave him you would have done it by now.”

How odd it felt to be uttering these words, which sounded so logical and were so wholly untrue.

“I’m sorry,” she repeated.

And so she was.

Well, and that was that.

I don’t suppose, really, it should have come as a surprise. A man, after all, is not a path; a path is a path, along with whichever man is on it. But putting words and meanings to thoughts and fears unspoken seemed as a death sentence, and at that moment I felt the life draining from our time together like soapy water swirling from a sink. And that is where I stood after she had gone, my hands on the edge of a white porcelain bowl, my face wet with confusion and despair, watching as the last remnants of what seemed a perfect life trickled to the rim of oblivion, hovering momentarily as if offering one last, fleeting glimpse of what I had known, before plummeting into the great chasm of what once was but shall never be. I seemed separated from myself as I leaned over the abyss, watching my arms as if they were the arms of another, supporting my weight but asking why was this my weight, why me whose thoughts connected to those distant arms, why me who had to reach with dead limbs to dry a face that would never again truly come dry. For a brief moment I felt as though it would not matter whether I turned and reached with my disconnected arm for that towel or stood there, indefinitely, waiting for time to end.

*

An hour ago my buzzer rang, and I thought—Jesus, I don’t want to talk to anyone right now. As I came toward the intercom I heard fingernails tapping lightly at the door. Adriénne was on the other side, cradling a plastic bag in her arms.

“I have to leaves, now,” she said, her big valise at her side.

“Adriénne, where are you going?” I asked her, but she only shrugged her shoulders. “Those is for you,” she said, handing me the bag.

“What’s this?”

“Maybe you needs those, too?” she said. “Hey, but you don’t has to find new apartments, yeah?” She lifted her hand and squeezed my arm gently, a brave smile trembling past difficult tears. Then she turned and left, pulling her suitcase behind her on its wheels. I watched her going down the steps one last time, the suitcase bouncing and clanging like the day she moved in.

When she had gone I opened the bag to find a bottle of Jack Daniel’s, a small card tied around its neck with a ribbon. “Thank You” was printed on the front. Inside two words were penned in her own hand: “my freend.”

I sit beneath a brooding sky and watch Adriénne from my fire escape, wondering what will happen to her now. Richard stands with arms folded, a statue in mind and body. The inchworm drops several stages in rapid succession, moving only in one direction; but for Adriénne the possibilities are endless.

THE END

You can read the rest of my published fiction online at my Fiction Page, which contains all my published work, both short stories and novel excerpts.

Anyway, it's always a good day when a story is published, and even nicer when it happens on our great nation's birthday. Happy Independence Day to all.

G.D.

11:22pm: The Park, The Whole Park, and Nothing But The Park

Central Park Carousel

Well, I taped the World Cup Final while I was sleeping, and woke up and rode out to the park to play some softball, as usual. There were a couple of guys hitting and fielding on field #3, and they invited me to join in, which I gladly did. Around noon some associates of a law firm came by with a permit for the field, seems they had a firm outing planned, including B.P., fielding, and a game to follow; but they invited me to hang around, which I gladly did. I even played an inning and a half of the game, until the rest of their peeps showed up, by which time I was more than happy to relinquish my post in the field. There was another game starting up on diamond 4, but I was ready to hit the road, and felt like tooling around the park a little bit with my camera.

First stop, Turtle Pond. There is a little observation deck on this side of the pond, just behind Delacourt Theatre and overlooking Belvedere Castle, and from there you can watch the turtles, fish, and birds conducting the business of existing in the Turtle Pond Conservatory. Here is a nice picture of the resident egret, who I found sunning himself on this side of the pond before taking to wing and nestling in the branches of a shade tree on the far side of the pond.

Resident Egret

Next I hopped on my rig and rode around the pond to Belvedere Castle, and stopped half-way around and snapped these photos of King Jagiello, with crossed swords astride his stallion, and this wonderful shot of the pond...

King Jagiello

The statue portrays the first Christian Grand Duke of Lithuania, King Jagiello, who united through marriage his native land to neighboring Poland. The monument depicts the moment at the Battle of Grunewald of 1410 when the King crossed over his head the two swords handed to him by his adversaries, the Teutonic Knights of the Cross.

Right across the path from the statue is a small rocky bank at the far end of the pond, from which I snapped this nice photo:

Turtle Pond

Then I rode up the path to Belvedere Castle, and took some photos from the observation deck; here's a nice shot across the pond of the Great Lawn:

The Great Lawn

From there I took the long way around, stopping at the Swedish Cottage Marionette Theatre before riding along the west side of the big loop, and heard some nice music coming from the bank along the lake, so I stopped to listen and purloined some nice photos of people boating and listening to the nice music played by, I was told, a guy named Dave:

Concert at the Lake

From there, I went down through the Hekshire softball fields to the Carousel, and took the panoramic shot at the top of this post, as well as this cute little pic of a horse & carriage passing along the loop:

The Headless Horseman

After that it was off to home, but first I stopped by one of my favorite haunts in the Park, the Sheep Meadow, where I can often be found tossing the disc around with Rand, Barnes, and the rest of the usual suspects. Anyway, I took a couple of panoramic shots and stitched them together, like so:

The Sheep Meadow

So, after that I tooled on back home and booted up that video of the World Cup Final, and got a real kick out of Ronaldo's two goals in Brazil's record 5th World Cup victory over Germany. AND, I got to watch live--as I booted up this blog and the accompanying Park Tour Photo Gallery--while the Yankees took the series with the Mets on a nice 3-hit shutout by Andy Pettitte (and, surprisingly, only the 3rd shutout in Pettitte's noteworthy career!). So, all in all, another great weekend here in the big apple, and I'm happy you were here to share it with me.